Steve’s Story, Part 1

Steve was a Wheaton College student when he started attending Church of the Resurrection in 2006. He alleges spiritually abusive behavior and pastoral malpractice by Resurrection leaders, including being targeted for excommunication despite adhering to church requirements that, as a gay person, he remain celibate. The story includes discussions of conversion therapy and the harmful teachings and practices surrounding it, which some readers may find disturbing.

Most names in this account are real; pseudonyms are noted with quotation marks.

In 2011, I was excommunicated from Church of the Resurrection because I had entered a same-sex dating relationship.

They didn’t tell me this at the time. In all of my conversations with Dcn. Keith Hartsell and Fr. Kevin Miller, the word “excommunication” was not used. I suspect this was an attempt to shield me from a word that might make the process seem final, when Dcn. Keith and Fr. Kevin’s hope was that I’d reconcile and be restored to Communion. (The phrase they used with me was that my actions had placed me in “profound peril.”) A friend of mine, who briefly served as an admin at the church, came across my entry a while later in the church’s database and realized my status was that I’d been “excommunicated by the bishop” in 2011.

Discernment

I started attending Church of the Resurrection in early 2006, while a student at Wheaton College. At Wheaton, I’d publicly come out as gay during my Freshman year, and had written and spoken intermittently as an advocate for LGBTQ+ students. Attending a Christian liberal arts college had acclimated me to a culture of suspicion toward LGBT students.

Part of what drew me to Rez was that it seemed to be for its LGBTQ+ people as much as it was for anyone else. I knew several LGBTQ+ students who attended Rez and served in ministries. A beloved and prominent worship leader at Rez was widely known to be same-sex attracted and was in what we would now call a mixed-orientation marriage; he often spoke to college student groups about his experience, which he described as a story of healing from broken desires. Several other lay leaders and clergy in the church seemed, at least to my eyes and ears, to be gay and celibate and celebrated.

It was powerful to attend a church where I could worship with, or receive prayer from, people who seemed like me, and who seemed to be fully integrated into their community. Their radically different interpretations of their experience of minority sexuality were, at the time, exhilarating to me, rather than threatening. Why should I expect others to come to the same conclusions as me about what their desires meant? I was invigorated by the diversity of faithful interpretation represented by the Rez community.

At this time, Rez was a part of AMiA, an Anglican offshoot formed in response to perceived liberalism in the Episcopal Church, including its affirmation of same-sex marriage. One of my friends, who also attended Rez, was curious and sent an email to Rez – was AMiA a reactionary body? If we are in Communion with TEC, why haven’t we tried to resolve our issues rather than form our own church? And what does Rez believe about homosexuality?

In a measured, thoughtful, and long response to my friend – a college student! – Rez member and Christianity Today managing editor Mark Galli outlined his own difficult decision to leave his local Episcopal church and join Rez, and attempted to make a case for why AMiA’s formation was the best option for theologically conservative Anglicans in the midst of a very difficult situation. My friend forwarded Galli’s response to me, said he was dissatisfied with this answer, and ultimately stopped attending Rez. At the time, I was puzzled by my friend’s leaving. I didn’t know what I believed yet and much of the complex church polity went over my head, but everyone involved seemed to be thoughtfully navigating a tough situation.

Now, reading Galli’s response to my friend, I’m primarily struck by one element of his reasoning. Galli said, “For Rez, one key issue was that the [TEC] diocese was actually undermining the key ministry of the church — its outreach to heal sexual dysfunctions, including homosexuality. While Rez was telling people that sexual aberrations were a sin that needed to be repented of, and a sickness that could be healed, the diocese was telling people (some of the very people who were coming to Rez for healing!) that their homosexuality was a gift of God. This was an untenable contradiction to endure and, in Rez’s view, a bold denial of biblical authority.”

My 2023 eyes are surprised to see Galli, in 2006, describe Rez’s “key ministry” as the healing of homosexuality. A contemporary piece by Jason Byassee in The Christian Century describes the various reasons why conservative clergy felt compelled to leave TEC for AMiA – for some it was the issue of bishops who did not affirm the bodily resurrection of Christ, for others it was the perception of relativism in matters of salvation. For the founders of Church of the Resurrection, and their allies, it was that they believed their ministry of healing for homosexuality was impeded by a perceived leftward drift in their diocese. But even back in 2008, as reflected in Byassee’s piece, clergy tended to be cagey about that part, at least on the record. In 2006, I’d never heard about healing from homosexuality preached from the Rez pulpit. This ministry of healing, if it still existed, was not advertised on the church’s website. I’m surprised that part of Galli’s email didn’t raise more red flags for me in 2006, but to be honest, I’m not sure I actually read the whole thing.

In 2009, I had begun a process of discernment around sexual ethics and was beginning to consider a position affirming of same-sex relationships. I hoped to discern while attending Rez, a community I greatly trusted and respected. Knowing Rez was conservative about sexuality was honestly a plus in this scenario – I wanted a check against my own conscience. However, I still had some lingering concerns about Rez’s origins as a ministry for the healing of homosexuality.

Rez did still have a healing ministry, called Redeemed Lives, oriented toward sexual brokenness, which I continued to hear whispers about but whose existence my Rez friends and I found confusingly ambiguous. It wasn’t advertised explicitly to same-sex attracted people, and it seemed like much of the church had gone through the ministry at one point or another, especially if they served in leadership. Meanwhile, the idea of healing from homosexuality had fallen out of vogue in much of evangelicalism. I assumed the same thing had happened at Rez. Obviously, Rez was conservative about homosexuality, but since I had not heard a message of healing from homosexuality preached from the pulpit, I hadn’t been particularly vigilant about it as a threat within the community up until this point.

Given all this, I was both wary of and drawn to Redeemed Lives. While I wasn’t seeking healing from my homosexuality, I did want to be bathed in prayer as I embarked on the discernment process for one of the most important decisions of my life. I’d received healing prayer on a few occasions at Rez and had found it to be a transformative experience. And sure, I would like to be healed of any sexual or emotional brokenness that might impede my discernment process. I decided to email Fr. Stewart for a meeting.

What I remember of my first meeting with Stewart is that I left feeling affirmed, reassured, and more than a little flattered. I remember this as a wide-ranging conversation – Fr. Stewart had read an essay of mine and was pleased I felt Resurrection was a positive community where my gifts were celebrated. We talked about the early days of Resurrection – how same-sex attracted people so quickly became the heart of Rez’s ministry. He was not shy about his conservative beliefs surrounding sexuality, nor about his conviction that the primary charism of Rez, especially in those early years, so soon after he’d lost his close gay friend to suicide, was the Holy Spirit’s work in healing people from homosexuality.

To this, I responded with skepticism and stressed that I wasn’t seeking healing from my homosexuality, and to the best of my memory, he met this with good humor and an invitation to lean in anyway. He stressed that Rez’s clergy held a variety of beliefs, albeit all conservative, surrounding theology of sexuality. He described how early on in Rez’s ministry, many same-sex attracted people married opposite-sex spouses; lately more same-sex attracted people remained single and celibate, and all were celebrated as examples of God’s faithfulness.

He was encouraging of my discernment process and encouraged me to be epistemologically diverse in my sources of knowledge. If I am reading the Scriptures and listening to the theological work of contemporary scholars and the church fathers, I should also be listening to the Spirit. He hoped that Rez could be a place where access to the Spirit was unbounded for me – unlike Wheaton, where the stuffy homophobia of leadership kept me at arms’ length from the work of the Spirit; unlike the affirming Episcopal church a Wheaton alumna had invited me to, where the Spirit is diluted by untruth. He gave me information about how to join the healing prayer program, Redeemed Lives.

In hindsight, I’m astonished at the pastoral trick shot Fr. Stewart achieved in this meeting. I entered the meeting with significant concerns about Rez’s suitedness to support me during a sensitive and challenging discernment process, and Stewart managed to convey numerous red flags in a way that was so warm and inviting that I felt trusted, affirmed, and ready to take a leap of faith.

I’d been conditioned to be wary of the anxious distrust of Wheaton administrators when my questions about sexuality were larger than they were comfortable with; I’d also been conditioned to expect ignorance and confusion from spiritual leaders who had no idea at all what to do with me. Here instead was humor and laughter and tons of experience and data, and no discomfort at all. I decided to trust Stewart and lean in.

Left to right: Fr. Stewart Ruch, Fr. Kevin Miller, Dcn. Keith Hartsell, Dcn. Karen Miller at Church of the Resurrection, 2010

Redeemed Lives

Participating in Redeemed Lives required a small deposit and a nine-month commitment. I started the program in Fall 2009, agreeing to remain in the Wheaton area, and at Rez, until Spring 2010. The commitment involved some daily prayer disciplines and a weekly group meeting lasting 3 hours on Tuesday nights. Three of my close friends decided to participate as well. One, like me, was gay; the other two were straight and in a relationship with each other.

The first information we received about the program was a packet that introduced Redeemed Lives as a “ministry for healing of sexual brokenness resulting from the fallout of the sexual revolution.” When we arrived for the first session, Deacon Phil, the leader of our class, walked us through how the next nine months would go. The sessions were split in half. First, the whole group of 30-40 participants and leaders sat together for lecture time. Then, we’d split into groups of six: two leaders/facilitators and four participants, for a time of focused healing prayer.

For the lecture portion of each evening, a television was rolled out into the conference room and we were shown pre-recorded talks given by Fr. Mario Bergner, the founder of the Redeemed Lives organization. We were told Fr. Mario was no longer attending Resurrection as he lived in Boston, but that his style of lecturing was too essential to the material, so we were to watch talks he’d given before he moved on.

Each week, the curriculum focused on a specific spiritual practice, such as lectio divina or the examen. Fr. Mario’s lecture style was discursive and tended to weave together three main elements: discussion of the week’s spiritual practice; discussion of psychological concepts related to narcissism and compulsive sexual behavior (heavily influenced by the work of reparative therapy psychologists like Joseph Nicolosi); and case examples, mostly of compulsive gay male sexuality, often from Fr. Mario’s own life and observations of his peer community. While the specific lectures we viewed may be lost to time, some examples of the Redeemed Lives workbook are included in screenshots below. However, even the workbook excerpts don’t do justice to the experience of a Fr. Mario lecture, a good example of which is available on Youtube.

The worldview presented in this video, and in the lectures we viewed, could be summarized like this: homosexuality is a narcissistic disorder resulting from a person’s maladaptive coping to a relational injury from childhood – some examples are sexual abuse, abandonment, an absent or emotionally troubled relationship with the father, an overbearing relationship with the mother, peer wounds caused by bullying or ostracization.

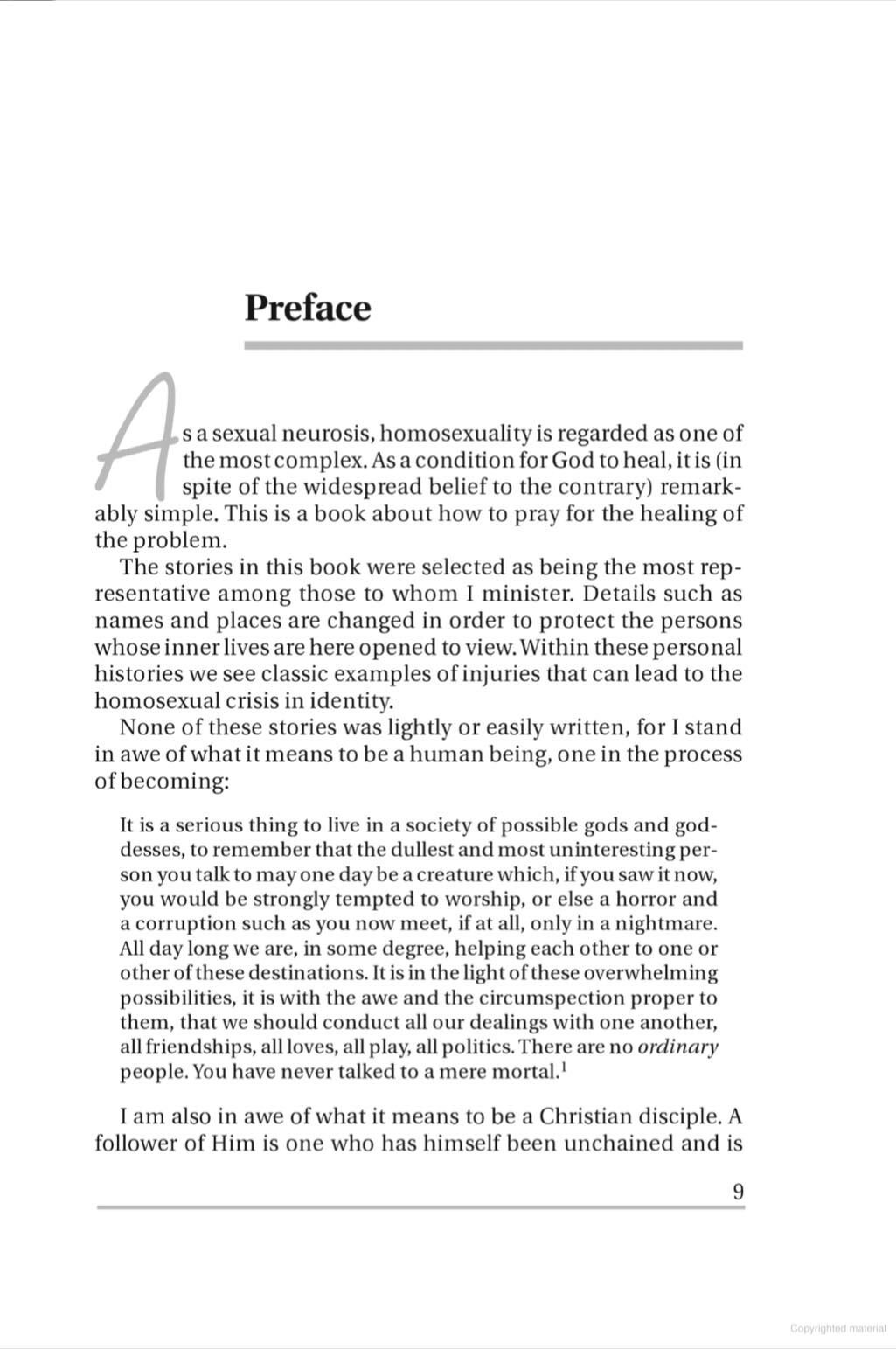

Father Mario shared his personal experience of a lonely childhood, troupe bonding with other gay men while living in “the gay lifestyle” in late adolescence, then a scare in the 80s with what he only referred to as “opportunistic diseases”, during which he had a supernatural experience of God while on a hospital bed, followed by a miraculous healing experience from physical ailment, leading to pursuit of relational healing under the tutelage of Leanne Payne.

Front and back covers and excerpt from Leanne Payne’s The Broken Image, copyright 1995

(I should mention that Redeemed Lives was promoted to the whole Resurrection community as a widely applicable pastoral care ministry for everyone dealing with sexual brokenness, emotional brokenness, mental illness, or “family of origin issues.” A large number of the participants in my class, such as my two heterosexual friends, did not experience same-sex attraction as far as I knew. Yet homosexuality was nearly the only form of sexual brokenness ever discussed in nine months of lectures.)

All of this immediately struck me as nonsense. I’d had minimal experience of ex-gay psychology and theology firsthand, but I’d read about it enough to recognize the similarities in Mario’s lecture to the writings of advocates of reparative therapy like Joe Dallas and Joseph Nicolosi. (While Redeemed Lives does not describe itself as an ex-gay ministry, its resources are often shared alongside ex-gay resources, and there are significant similarities in teaching and practice between RL and ex-gay ministries. And while the official teaching of a program like RL would likely align with the post-ex-gay saying “the opposite of homosexuality isn’t heterosexuality; it’s holiness” – Mario often slipped into speaking of those who “successfully move out of homosexual identification into heterosexual identification.”)

I had experienced so much good teaching at Rez, and after years spent deepening my relationship with Rez, I was surprised and devastated at exactly how bad this teaching really was, especially since Redeemed Lives was often discussed with hushed tones, as if it were the holiest of holies in the community’s pastoral care ministry. Indeed, moving through RL seemed to be an unofficial prerequisite to any type of pastoral ministry at Rez.

The program was not without its merits. The small group portion, which came after the lectures, involved an hour of healing prayer. In my group, four young men were participants, and two men were leaders. The two leaders were gentle, kind and spiritually mature same-sex attracted men who had both been living as celibate members of the community for years. At least in the small group setting, the lack of distinction between gay and straight participants was radical and meaningful for me, as someone who had experienced so much distrust in evangelical circles as a same-sex attracted person. In Redeemed Lives, sexual brokenness did not discriminate, nor did the Holy Spirit.

At the time, I suspected I was smart enough and catechized enough to not be affected by hearing false ex-gay teaching, so I tried to view my participation as a kind of embedded journalism. But, ten years later, I now understand that I vastly overestimated my strength: being steeped in ex-gay teaching for nine months, during a vulnerable time of spiritual healing and growth, broke my brain.

Since my homosexuality is not a narcissistic personality disorder (because that’s just not true for most people), but since I do indeed experience sexual brokenness (who doesn’t?) Mario’s teaching contained deep truths wrapped in multiple lies that were targeted directly at demolishing the egos of people like me. In my experience, friends who underwent typical ex-gay teaching had internalized a fundamental lie about the imago dei: the way you are now is not good, but God can change you into something good. The lie I internalized due to my time at Redeemed Lives was more sophisticated, but still a lie: you were created in the image of God, but you – specifically those of you whose sexual desires do not align with the norm – have a perception of reality that is so deeply broken that you have no direct access to revelation from God about your true, created self. You must disbelieve everything you believe to be true about yourself and trust instead this narrow, specific teaching, developed in the Western Suburbs of Chicago in the 1990s, relying heavily on data that has been disproven by numerous reputable scientific bodies. If you doubt that we have your best interest in mind, that is also due to your neurosis.

The cumulative effect of this teaching left me with a profound doubt in my own ability to receive any kind of revelation from God, whether through Scripture or experience or tradition. Perhaps my own neurosis was so deep that I was like the emperor with no clothes – not only unaware of the truth, but unaware of how unaware I was. Perhaps how I saw Fr. Mario – as well-intentioned but dangerously wrong-headed – is how God saw me. Perhaps, in the words of gay Catholic theologian James Alison, I “[did] not correspond with creation” at all, but instead every moment I received my created, homosexual self as a gift from God, I was simply incorrect. Perhaps my refusal to lean into Fr. Mario’s teaching was preventing the miracle that would let me finally see the light. Perhaps my growing desire for a self-sacrificial Christian marriage to a man was putting pretty clothes on something selfish and cruel. The amount of intellectual gymnastics I performed to avoid simply acknowledging that this priest I’d never met was probably wrong!

And yet, I can’t deny that tremendous spiritual growth and healing took place while I was receiving prayer in Redeemed Lives. Re-reading old journals, I see a frightened boy who began, through a sort of Holy unrest, to be capable of love. The Holy Spirit showed up. The Holy Spirit did not, however, convict me that my sexuality was a narcissistic personality disorder caused by a formative relational injury from which I could repent and heal – because that’s simply false.

I finished the Redeemed Lives program in Spring 2010. Despite my challenges with Redeemed Lives for the past nine months, I was otherwise flourishing at Rez. I’d joined the choir, and it was a really good choir. On some weeks, I helped out by running sound before and after services or occasionally assisting the worship team on stage. These ministries helped me build relationships within the church, especially those with older folks and families – forms of relationship I missed, as a recent college grad surrounded by twenty-somethings.

Pages from the Redeemed Lives workbook, contributed by a fellow participant

Discipline

At the same time, an LGBT alumni group emerged at my alma mater, Wheaton College, called OneWheaton. During OneWheaton’s organizing phase, in late 2010 and early 2011, I got to know a wider range of queer folks than I ever had – including affirming Christian gay couples. While I was not affirming at this time, my theological commitments to church unity and the creeds held that these people are still part of the church, and I started to find myself wishing I could bring my increasing number of non-Christian or Christian-curious gay friends to Rez – because it was such a good church, and many of them were curious about God. But I knew this was not possible, which furthered my disillusionment. What good is a church you can’t invite your community to?

I also started to fall for a friend of mine who reciprocated my feelings, and we started to talk about dating. While not fully affirming yet, I was not opposed to entering into a chaste dating relationship as a part of my discernment process. I viewed this as a sort of qo’helet experiment, after the author of Ecclesiastes, who sought out life experience as a way of seeking the heart of God.

At some point during all this I sought out Dcn. Keith Hartsell for pastoral advice, but he was unable to provide competent care or guidance. Regarding the man I had feelings for, he tended to respond to my questions with tangential redirects. “I understand, man, you just want to get in his pants.” When I clarified that I was seeking out a chaste dating relationship at this stage, he changed tactics. “You know, when you describe him, I feel like you’re describing yourself.” I realized he was moving through a sort of ex-gay playbook here, hinting at a peer wound that made me seek out men who looked similar to me.

Regarding my internal conflict about bringing my non-Christian gay friends to church, no amount of clarifying could get Dcn. Keith on the same page. “Steve, we’d absolutely love for you to invite them. I don’t see the problem here.” A continued undercurrent in Keith’s pastoral care was that he had no shortage of time for me, but until I was ready to engage with his specific toolkit of psychosexual healing, we weren’t going to get anywhere, and he tended to impatiently redirect me back in that direction. Most of my questions were met with a sort of gentle exasperation, the kind you might use with a sullen teenager, as if to say, “Are you ready to be honest with me yet?” But I thought I already was being fully honest. I left the meeting with Keith feeling frustrated and a little crazy.

I ended up calling things off with the guy I’d fallen for. I felt certain that dating him would mean I’d have to leave Rez, and I wasn’t ready to do that yet. Meanwhile, relationships I was forming with mature gay Christians – both affirming and celibate – continued to be pastoral in ways the clergy at Resurrection could not.

The OneWheaton group was planning a letter drop on Wheaton’s campus in Spring 2011, to announce itself to students and the public as an affirming LGBT alumni association. I felt a “which side are you on?” moment approaching. I wanted to participate in what OneWheaton was doing, even if I wasn’t fully on board yet with affirming theology. I felt deeply convicted about affirming that gay Christians are part of the church and should not be de-platformed.

I decided to choose chaos and participate. I attended the letter drop, and handed out OneWheaton’s letter, even though I would’ve preferred it to be loaded with far more caveats and nuance. “You are not tragic,” the letter read. “Your desire for companionship, intimacy and love is not shameful.” Given what I’d just experienced at Rez, it’s not hard to imagine why, in spite of my quibbles, this message deeply resonated with me.

The letter drop, including a photo of me at the event, made national news. I decided I should post something on my blog, since the story had spread farther than I expected. Here’s an excerpt of what I posted:

“I’m currently affirming of same-sex unions, and am gayer than I've ever been, without any of the accompanying ‘celibate’ or ‘struggling’ tags.”

I’m honestly a little shocked at how explicitly affirming this post was, since my memory tells me that internally I was still far from affirming at this point. (You can decide for yourself how it comes across; there’s a screenshot of the whole post below.) I was just starting my career, and I wanted to err, early and often, on the side of being for queer people – all queer people. So I figured: I don’t know how long I’ll be in between views, but if people are going to assume something, I’d prefer them to assume I’m for gay people. My blog had a few dozen followers and had been inactive for over a year, so this was primarily a symbolic gesture for me, since not many people saw it.

Steve’s April 29, 2011 blog post

“Robert” and “Susan,” friends and musical collaborators of mine from college who were now in ministry at Rez, did see the post. “Susan” was a frequent worship leader at Rez; “Robert” was in the process to be ordained as a priest. Each of them wrote to me in response to my post. “Susan’s” email was long, searching, and open-ended. “I want to hear what you think about this OneWheaton thing.” “Robert’s” email came later and was briefer: “Susan said she emailed back and forth with you a little bit about OneWheaton. I'd love to hear your thoughts on it.” I set dates with both of them, but “Robert” confirmed and “Susan” flaked.

I had a weirdly formal meeting with “Robert” and then a week later I had a voicemail from Fr. Kevin, a more senior Resurrection priest. He invited me to meet with him and Dcn. Keith “on May 25th, at 3PM. Please let us know if you are available at that time.” I realized I was being called into the principal’s office.

Read Part 2 of Steve’s Story.