Organizational Impression Management in the Church

by Abbi Nye

When churches face a crisis, they are presented with two choices in their public response. They may choose truth and transparency, even if it negatively impacts them, or they may opt for impression management tactics that twist the facts to portray a positive status or image.

Research indicates that organizations’ predominant behavior in crisis situations is to utilize organizational impression management strategies. Churches are not immune to this temptation. Located at the intersection of marketing, psychology, and communication, Organizational Impression Management (OIM) is a useful framework for understanding how churches respond to negative events.

This spring, ACNAtoo published a guest blog post that contrasted the theology of glory and the theology of the cross. A theology of glory is “a way of perceiving God’s work in the world through progress, achievement, victory, power, strength, and glory. Where such things are to be found, the theologian of glory assumes God’s blessing and favor. Where such things are absent, the theologian of glory assumes God’s curse.” Churches who adhere to a theology of glory often reflexively employ OIM strategies to manage their image since they only see God’s work in the glory.

It is important to note at the outset that the role of intention is sometimes unclear when organizations and individuals respond to a crisis with OIM tactics. Researcher and advocate Wade Mullen notes that OIM strategies are “sometimes highly calculated and at other times manifested semi-consciously or even unconsciously.” When these strategies are manifested unconsciously, it can often be the “result of individuals or organizations operating in accordance with predetermined roles and expectations. The behavior is not so much a product of one’s character or personality as it is a product of one’s public role. For example, particular professions, such as the clergy, demand that individuals conduct themselves in a certain manner so they do not disgrace their role.”(1)

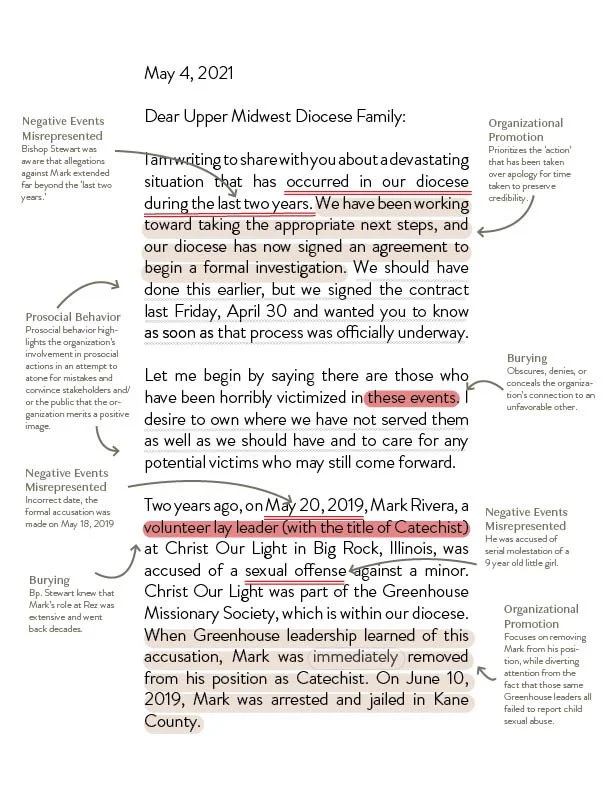

The May 4, 2021 Diocesan letter from Bishop Stewart Ruch announcing an investigation into sexual abuse and mishandling is a prime candidate for case study analysis utilizing the OIM framework because it was the first official communication congregants received about the situation. It was posted on the Diocese of the Upper Midwest website and distributed through clergy to their congregations via email. The letter is also a contender for this analysis because the factual inaccuracies it contains were never corrected, despite immediate and urgent requests from survivors and their advocates. Over a year later, the province has not communicated corrections of these inaccuracies, so they continue to stand as the official communication to date. For most people in the Diocese, this letter marked the first communication of any kind about the allegations of abuse against Mark Rivera that were reported to Church of the Resurrection leaders starting two years earlier.

We offer this letter and the corresponding analysis as an educational resource for all ACNA leaders and congregants. Bolded terms throughout this analysis refer to OIM terminology and are included in a glossary at the end of the piece. We are particularly indebted to Wade Mullen’s work on OIM in the church, both in his 2018 dissertation and in his book Something’s Not Right: Decoding the Hidden Tactics of Abuse--and Freeing Yourself from Its Power, for the analysis shared in this case study.

Bishop Stewart’s Letter Regarding Devastating Situation in Diocese

One of the first things that strikes the reader with background knowledge is the selective disclosure of information. The letter uses a high level of specific detail when describing what the Diocese has done, while leaving the statements about survivors’ abuse vague and understated. This is a common tactic seen in many churches facing crises, including Willow Creek Community Church. Wade Mullen perceptively notes in his book Something’s Not Right that:

“...organizations often try to save face after a scandal by overcommunicating some facts and undercommunicating others to the “audience.” Whether the audience is the public, other members of the organization, the media, victims, or the civil authorities, the abuser and the performance teams around them omit or undercommunicate what Goffman calls “disruptive information,” facts that threaten the audience’s image of the abuser. At the same time, the abuser and performance teams selectively disclose information that improves the abuser’s image. It’s information control. All of the actors do what they can to keep the audience from gaining disruptive information that would redefine what they’re seeing.” (2)

In the opening paragraphs, the letter employs an OIM tactic called Negative Events Misrepresented, which includes “statements offered in regard to a particular event [that] were taken out of context or were untrue in some way.” (3) This misrepresentation includes incorrect dates and statements that obscure the fact that Bp. Ruch was aware of allegations against Mark Rivera which extended far beyond the “last two years.”

Organizational Promotion tactics are highlighted in the opening paragraphs. These tactics consist of behaviors that present the organization as being highly competent, effective, and successful. We see an example of this where the letter sandwiches the vague apology over the long-overdue investigative action between very specific details about signing an agreement on Friday, April 30.

A third key strategy used in the opening paragraphs is Prosocial Behavior. These tactics are “designed to protect the image of the organization by diluting, rather than refuting, negative claims about the organization. This tactic does not address claims directly but instead attempts to divert attention to the perceived positive attributes of the organization.” (4) Phrases like “we wanted you to know as soon as that process was officially underway” imply transparency with congregants and divert attention from the lack of transparency that dragged on over two years. Similarly, “I desire to own where we have not served them well” glosses over the real harm done to the survivors and instead makes the writer sound genuine and credible.

"A linguistic choice that “obscures, denies, or conceals the organization's connection to an unfavorable other" is called a Burying tactic. This tactic can be easily seen in how Mark Rivera's abuse of multiple individuals is downplayed as simply "these events". (5)

The third paragraph sets the tone with an incorrect date. The letter follows up with additional Burying tactics: as a longtime personal friend of Mark Rivera, Bp. Ruch knew that Mark's involvement with Church of the Resurrection was extensive and went back decades. Similarly, “sexual offense” obscures the full scope of the abuse, which includes both rapes of an adult and the serial molestation of a 9-year-old child.

We see Organizational Promotion in the assertion that Mark was immediately removed from his position, while diverting attention from the fact that those same Greenhouse leaders all failed to report child sexual abuse.

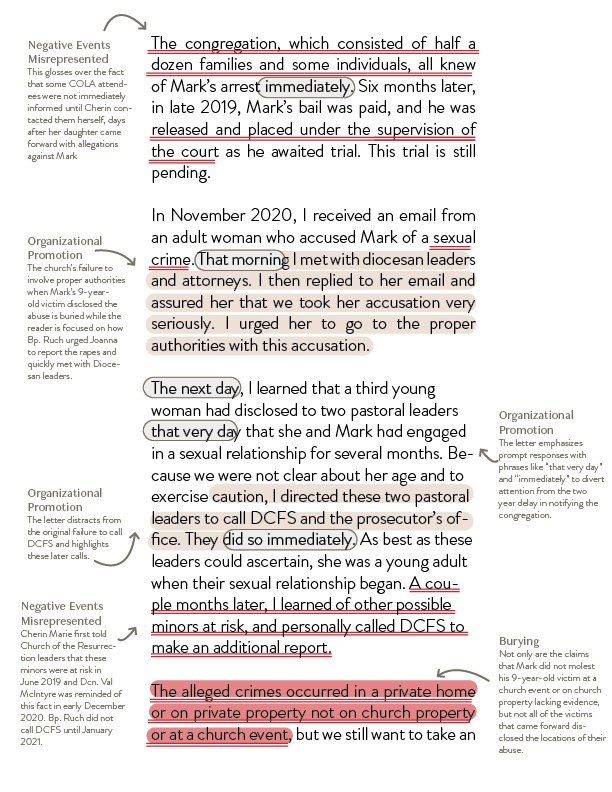

The next paragraph is also riddled with Negative Events Misrepresented. It glosses over the fact that some COLA attendees were not informed of the allegations during the three weeks Mark was freely attending COLA with access to their children.

Nor does it address the fact that UMD Chancellor Charles Philbrick was helping Mark find discounted legal representation during those weeks. Furthermore, the phrase “supervision of the court” implies that the public was protected. Instead, Mark continued to interact with minors and is currently awaiting trial for reportedly raping Joanna Rudenborg while out on bond.

Joanna’s November 2020 disclosure of two alleged rapes and years of abuse is generalized as a “sexual crime.” The church’s failure to involve proper authorities when Mark’s 9-year-old victim came forward is Buried while Organizational Promotion focuses the reader on how Bp. Ruch urged Joanna to report the rape and quickly met with Diocesan leaders.

Moving into Organizational Promotion, the announcement implies general thoroughness regarding DCFS, even though Cherin Marie had alerted the church to several additional victims two years prior. The use of phrases like “that very day” and “immediately” divert attention from the two year delay in notifying the congregation.

Misrepresenting Negative Events is employed again as the letter states that Bp. Ruch learned about other minors at risk “a few months later.” Cherin Marie first told Church of the Resurrection leaders that these minors were at risk in June 2019 and Dcn. Val McIntyre was reminded of this fact in early December 2020. Bp. Ruch did not call DCFS until January 2021.

In the next paragraph, Bp. Ruch is further distanced from Mark Rivera through what appears as Burying and Misrepresenting Negative Events. His claims that Mark did not molest the 9-year-old victim at a church event or on church property are wholly unsubstantiated. Not all the reported victims that came forward (including the 9-year-old) disclosed the locations and exact details of their abuse to the church. This assertion is incomplete at best, and misleading at worst.

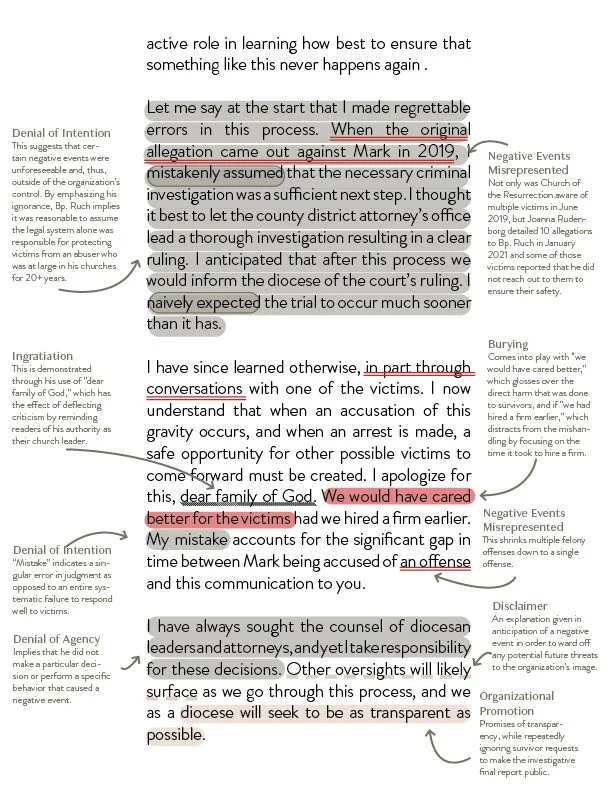

The assertion that Bp. Ruch made regrettable errors because of his ignorance utilizes a Denial of Intention strategy known as the Excuse. Mullen describes this type of strategy as statements that “suggest that certain negative events were unforeseeable and, thus, outside of the organization’s control” (6). By emphasizing his ignorance, Bp. Ruch implies it was reasonable to assume the legal system alone was responsible for protecting victims, yet the abuser was at large in his churches for 20+ years.

Moreover, the letter Misrepresents Negative Events by implying there are only 3 allegations. Not only was Church of the Resurrection aware of multiple victims in June 2019, but Joanna Rudenborg detailed 10 allegations to Bp. Ruch in January 2021 and some of those victims reported that he did not reach out to them.

The paragraph concludes with a number of intersecting OIM strategies. Ingratiation is demonstrated through his use of “dear family of God,” which has the effect of deflecting criticism by reminding readers of his authority as their church leader. Burying comes into play with “we would have cared better,” which glosses over the direct harm that was done to survivors, and “if we had hired a firm earlier,” which distracts from the mishandling by focusing on the time it took to hire a firm. Two strategies are squeezed into the last sentence: “my mistake” is a Denial of Intention Excuse since “mistake” indicates a singular error in judgment as opposed to an entire systematic failure to respond well to victims, and “an offense,” which Misrepresents Negative Events by shrinking multiple felony offenses against 2 victims down to a single offense.

The next paragraph continues with more Excuses in the form of a Denial of Agency. In this strategy, “Organizations may argue that they themselves did not make a particular decision or perform a specific behavior that caused a negative event.” (7) This is followed immediately by Disclaimers, which are “explanations given in anticipation of a negative event in order to ward off any potential future threats to the organization’s image.” (8) The finishing touch returns to Organizational Promotion with promises of transparency, all while repeatedly ignoring survivor requests to make the investigative final report public.

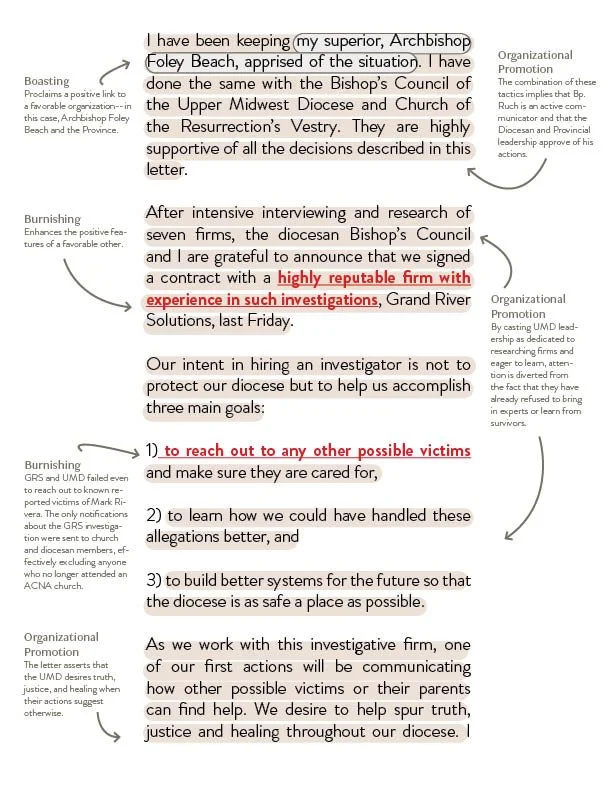

The writer follows this with more Organizational Promotion and Boasting. Boasting “proclaims a positive link to a favorable organization”--in this case, Archbishop Foley Beach and the Province. (9) The combination of these tactics implies that Bp. Ruch is an active communicator and that the Diocesan and Provincial leadership approves of his actions. Mullen notes:

“...impression management behavior is directly tied to an attempt to project or preserve a desired image, an image that is threatened during a crisis and an image that is often shared by those in the highest levels of the organization’s hierarchy. In other words, this behavior is driven by individual identities that are tied to organizational identities that are threatened during a crisis. A threat to the organization’s image is therefore a threat to the images of the individuals who lead that organization.” (10)

The letter communicates organizational competency and efficiency with references to intense interviewing and research of investigative firms while glossing over the research that was conducted independently by Joanna Rudenborg and other advocates, and then ignored in favor of Grand River Solutions. The Burnishing strategy is utilized as GRS is referred to as a reputable firm, despite the fact that their standards are in complete opposition to the carefully written survivor requests (not to mention the survivor-trusted gold standards of GRACE). Burnishing “enhances the positive features of a favorable other.” (11)

The three goals outlined for hiring an investigative firm are a further example of Organizational Promotion:

1) to reach out to any other possible victims and make sure they are cared for,

2) to learn how we could have handled these allegations better, and

3) to build better systems for the future so that the Diocese is as safe a place as possible.

By casting UMD leadership as eager to learn, attention is diverted from the fact that they have already refused survivors’ repeated attempts to educate them on how to do better. The letter also Burnishes GRS’s reputation as a firm that can reach out to possible victims, when the UMD and GRS made no effort to reach out to survivors, even past members who reported abuse by Mark Rivera. Communications about the investigation were only circulated through church and diocesan mailing lists, effectively excluding anyone who no longer actively attended a UMD congregation.

The Organizational Promotion continues in the next paragraph where it asserts that the UMD desires truth, justice, and healing when their actions suggest otherwise. The paragraph finishes with a Disclaimer that promises communications with updates and corrections, yet no communication occurred between this announcement and Joanna Rudenborg's first Twitter post almost two months later, despite the fact that survivors immediately informed Bp. Ruch of numerous inaccuracies in the announcement.

The paragraph describing Mark Rivera’s involvement with Church of the Resurrection combines Burying and Negative Events Misrepresented strategies. Mark continued attending Church of the Resurrection after 2013, because Christ Our Light Anglican met on Saturday evenings. Mark even attended Church of the Resurrection while out on bond.

The letter further Buries all of Mark’s volunteer positions at Church of the Resurrection, despite the fact that UMD was aware of the extensive roles Mark held over the years. Furthermore, highlighting Mark’s positions as unpaid implies that giving people unpaid authority positions somehow makes the Church less responsible when they abuse that position.

Describing Mark’s extensive abuse in the next paragraph as “harm” is a clear example of Prosocial Behavior. Prosocial behavior is “designed to protect the image of the organization by diluting, rather than refuting, negative claims about the organization.” (12) Harm is a tepid word that illuminates the threat that Mark’s abuse poses to the church’s image by downplaying the full extent of the abuse.

The letter then appeals to the readers for sympathy with Supplication tactics, which “portray an image of dependency and vulnerability for the purpose of acquiring help, favor, or sympathy from others.” (13) The letter centers the distress experienced by church leaders and then claims the Diocese has provided care for survivors, despite the fact that Cherin Marie emailed Bp. Ruch on May 1 (three days before this letter was published) to outline significant pastoral care failures by Dcn. McIntyre and Church of the Resurrection

The final paragraph contains Ingratiation tactics, which are “designed to make the organization appear more attractive thereby gaining the approval of an audience.” (14) Ingratiation in a church context often takes the form of spiritual language to gain favor with their religious readers. Hillsong Church, for example, employs this same strategy in their announcement of Rev. Brian Houston’s resignation. The readers of this Diocesan letter are encouraged to find comfort by leaving the matter in God’s hands and not taking any direct action. The letter exudes a theology of glory instead of a theology of the cross.

Conclusion

The thorough application of OIM tactics in this letter distracts from the significant destruction caused by Mark Rivera’s abuse and paints a positive image of Church of the Resurrection’s leadership. Readers come away from this letter with the overall impression that Bp. Ruch is leading the Diocese well and that Grand River Solutions will handle things going forward.

However, there is ample reason to pay attention to the man behind the curtain. Things are not as they appear. Whether employed consciously or subconsciously, the OIM strategies illustrated in this letter suggest a church culture that cannot tolerate a negative image because it disrupts its theology of glory. This is especially apparent in the way that Mark Rivera’s abuse is minimized, since Rivera’s prolific and chronic abuses threaten Church of the Resurrection’s theology of glory.

When one understands the rhetoric of image management employed in this letter against the evidence in the Timelines provided by survivors, the OIM tactics stand out clearly. This letter unsettles more than it assures.

Abbi Nye is an archivist in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She holds a BA in Biblical and Theological Studies from Wheaton College and an MLIS from UW-Milwaukee and enjoys studying the influence of liberation theology on Roman Catholic priests in Milwaukee’s civil rights movement. When she’s not teaching about primary source literacy, you’ll find her watching the latest Kdrama or baking macarons with odd flavor combinations for her husband and son.

Glossary

Excerpted from Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation).

Boasting: Proclaims a positive link to a favorable organization (e.g. a church comparing itself to another successful church).

Burying: Obscures, denies, or conceals the organization’s connection to an unfavorable other whereas blurring obscures or offers disclaimers for its negative link to a favorable other, often by way of strategic omissions.

Burnishing: Enhances the positive features of a favorable other (e.g. a church praising the successes of another church it compares itself to).

Disclaimer: An explanation given in anticipation of a negative event in order to ward off any potential future threats to the organization’s image. Its main purpose is to justify a future action, decision, or event that will generally be viewed as negative.

Denial of Agency: Organizations may argue that they themselves did not make a particular decision or perform a specific behavior that caused a negative event. The goal is to lead the stakeholders to believe that they did not produce the negative event in question.

Denial of Intention: This strategy suggests that the organization would have made a different decision had it been informed of the potential consequences. The intended result is that the targets of these statements will not view the organization as responsible for the negative event.

Ingratiation: Ingratiation tactics can be other-focused or self-focused. Tactics focused on others use compliments, flattery, favor rendering, and opinion conformity to enhance their target’s level of liking. Ingratiation tactics focused on one’s self utilize statements designed to make the organization appear more attractive thereby gaining the approval of an audience.

Negative Events Misrepresented: Statements that take facts out of context or are untrue in some way.

Organizational Promotion: Behaviors that present the organization as being highly competent, effective, and successful.

Organizational Handicapping: Efforts by the organization to make success appear unlikely in order to provide a ready-made excuse for failure. By suggesting that the organization is handicapped in some way, the organization can then use that perception as an excuse for its failure.

Prosocial Behavior: Demonstrating to the public that the organization is committed to socially acceptable behaviors, beliefs, and values. This tactic does not address claims directly but instead attempts to divert attention to the perceived positive attributes of the organization.

Supplication: Employed by the organization to portray an image of dependency and vulnerability for the purpose of acquiring help, favor, or sympathy from others.

Endnotes

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Mullen, Wade. (2020) Something's not right: Decoding the hidden tactics of abuse--and freeing yourself from its power. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale Momentum.

Caillouet, R. H. (1991). A quest for legitimacy: Impression management strategies used by an organization in crisis (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (UMI 9200053). In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

McDonnell, M., & King, B. (2013). Keeping up appearances: Reputational threat and impression management after social movement boycotts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(3), 387–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839213500032. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, K. M., Turnley, W. H., & Gilstrap, J. B. (2008). A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1080–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324325. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Tedeschi, J. T., & Reiss, M. (1981). Identities, the phenomenal self, and laboratory research. In J. T. Tedeschi (Ed.), Impression management theory and social psychological research (pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Academic Press. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Ibid.

Mohamed, A., Gardner, W., & Paolillo, J. (1999). A taxonomy of organizational impression management tactics. Advances in Competitiveness Research, 7(1), 108–130. Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Mohamed, A., Gardner, W., & Paolillo, J. (1999). A taxonomy of organizational impression management tactics. Advances in Competitiveness Research, 7(1), 108–130. Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). 44. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Mohamed, A., Gardner, W., & Paolillo, J. (1999). A taxonomy of organizational impression management tactics. Advances in Competitiveness Research, 7(1), 108–130. Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

McDonnell, M., & King, B. (2013). Keeping up appearances: Reputational threat and impression management after social movement boycotts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(3), 387–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839213500032. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). 49. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view

Caillouet, R. H. (1991). A quest for legitimacy: Impression management strategies used by an organization in crisis (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (UMI 9200053) and Mohamed, A., Gardner, W., & Paolillo, J. (1999). A taxonomy of organizational impression management tactics. Advances in Competitiveness Research, 7(1), 108–130. In Mullen, Wade. (2018) Impression management strategies used by evangelical organizations in the wake of an image-threatening event (Doctoral dissertation). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rXrd8MYay5Vg5s7JXFx7S91hDTlm1CVX/view